The relevance of logistics in the Circular Economy

The transition to a circular economy, requires us to redesign chains and learn new lessons about driving circular value networks. In such a circular economy, we no longer simply produce products and regularly order raw materials to do so. No, in a circular economy, products and materials are linked in a complex whole. As more raw materials for our products come out of the market as return flows, business models change significantly.

Changes in business models range from identifying new value networks based on innovative partnerships to predicting return flows and planning and coordinating production and transport activities. This is why logistics is so relevant to the transition to a circular economy. Hence TKI Dinalog is taking a leading role in research and innovation to support this transition.

The logistics paradox in the circular economy

It is becoming increasingly important to collect products and residual streams separately to ensure that they can be processed in an efficient and responsible way. This is also the experience of PreZero indicates Iwan te Winkel, director of Collection & Operations at PreZero Netherlands.

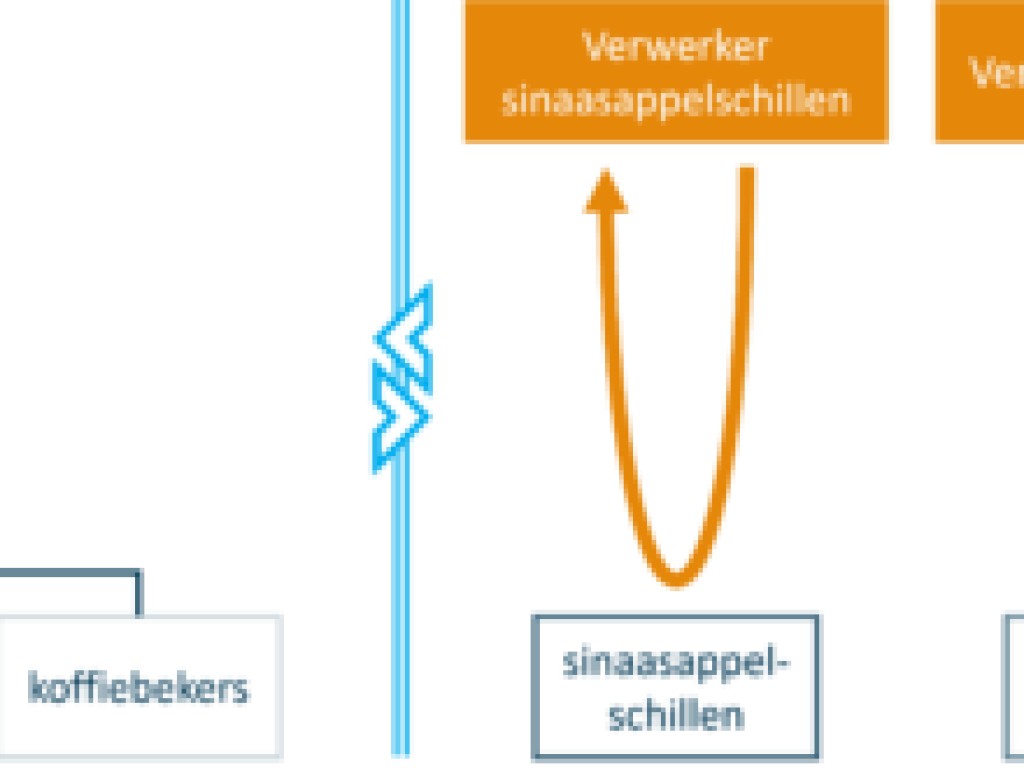

Industrial waste is a good example. You can collect orange peels, coffee grounds, plastic or coffee cups separately, but then the question is how best to organise this logistically. For instance, is it convenient to set up separate logistics for this, or can it be combined in a good way?

We are also seeing more and more producers and startups withdrawing specific products and waste streams from the market. On the one hand, this is due to sectors with a extended producer responsibility (EPR) that makes a producer want its own product back. On the other hand, this is due to new business models around the valorisation of specific waste streams.

The logistics paradox in the circular economy

It is becoming increasingly important to collect products and residual streams separately to ensure that they can be processed in an efficient and responsible way. This is also the experience of PreZero indicates Iwan te Winkel, director of Collection & Operations at PreZero Netherlands.

Industrial waste is a good example. You can collect orange peels, coffee grounds, plastic or coffee cups separately, but then the question is how best to organise this logistically. For instance, is it convenient to set up separate logistics for this, or can it be combined in a good way?

We are also seeing more and more producers and startups withdrawing specific products and waste streams from the market. On the one hand, this is due to sectors with a extended producer responsibility (UPV) that makes a producer want its own product back. On the other hand, this is due to new business models around the valorisation of specific waste streams.

At its core, a circular economy requires clean residual streams to enable high-quality reuse of products ('reuse') or materials ('recycle'). To make this possible, everyone is looking for an affordable logistics system. In this, on the one hand, even the smallest residual flows are treated separately, while on the other, we are also looking for efficiency by scaling up, combining and/or cooperating. This is what Iwan te Winkel calls "the logistics paradox of the circular economy" and is the challenge he deals with on a daily basis.

This logistics paradox falls into three challenges; namely those of the actor versus the system, data, indicators and transparency, and the social side of the circular economy.

The actor versus the system

The above outline of goods flows in a circular economy shows that a logistics demand arises from every possible residual flow, for which currently a logistics solution is also often sought separately by the actors involved in their own sector. However, for a logistics system that is sustainable in all respects, it is important to think not only from the actors' point of view, but also from the whole system in which they act. It is important to identify synergies, seek collaborations and design logistics efficiently. The challenge is to set up an effective and efficient logistics system for the fragmented logistics needs of individual actors.

The challenge that many companies that are already operating circularly experience in this is to scale up their initiative to become players of significance in the entire market.

Data, indicators and transparency

In view of national and international circularity targets, it is important to understand how circular we actually are. What percentage of materials used is reuse-based? What proportion of discarded clothes or electronics finds a way to a second level? What proportion succeeds after a repair or remanufacturing process. What proportion is still recycled in any case?

These are questions we should actually be able to answer for different product groups in order to take action or develop policies based on them. Without a good baseline measurement, it is difficult to talk about targets for 2030 or 2050. There seem to be initiatives in different sectors and/or companies to develop indicators, but a certain uniformity would be important.

In addition, ownership of the underlying data is a major challenge: often the data is perceived as competitively sensitive and not shared. Incidentally, this is not only true for our circular future, but is already often a pressing issue today. It is obvious that solutions under development can also be useful for circular initiatives.

The social side of the circular economy

The transition to a circular economy is clearly a challenge for the coming decades. But how we enter this transition has many social and socio-economic implications. For example, as clothing shops transition to more circular business models, fewer garments will end up in thrift shops, reducing the access of a section of the population to an affordable alternative to new clothes. We see a similar development in food chains, where supermarket chains, for example, are getting better and better at reducing food waste. This in turn means that food banks see the number of donations drop, while on the other hand they see the demand for food aid rise.

In general, we need to ensure that steps towards circularity do not have undesirable socio-economic side effects, but may even simultaneously produce positive development here.

So, the paradox and more

From this perspective, it is clear that logistics plays an important role in (the transition to) a circular economy. The logistics paradox is an important component of this. During the 2023 edition of the National Conference of the Circular Economy, it became clear again that there is still a lot of work to be done to address the logistics challenges.

The relevance of and need for early thinking about new logistics concepts for the circular economy go beyond this paradox. For instance, there are issues about the predictability, reliability and effectiveness of raw material supply and logistics aspects associated with servitisation and the other steps on the R-ladder: Repair, Refurbish, Remanufacture and Repurpose. Here, too, there are issues of scaling up and sourcing, for example. This gets to the heart of what logistics is and means.

Therefore: research and innovation

Hence TKI Dinalog, together with its network partners, is strongly committed to research and innovation. In a recent funding round in cooperation with the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, a number of projects were awarded to consortia that will delve further into these issues in the coming years. LINCIT, a project on circular business ecosystems (led by TU/e), and LogiCELL, a project focused on the logistics principles and basic forms needed for a circular economy (pulled by WUR).

-

This post is based on the Table Session on Logistics in the Circular Economy organised by TKI Dinalog in cooperation with Wageningen University and PreZero during the Week of the Circular Economy 2023 in Zwolle. TKI Dinalog warmly thanks Iwan te Winkel (PreZero) and Renzo Akkerman (WUR) for their efforts before, during and after this Table Session.